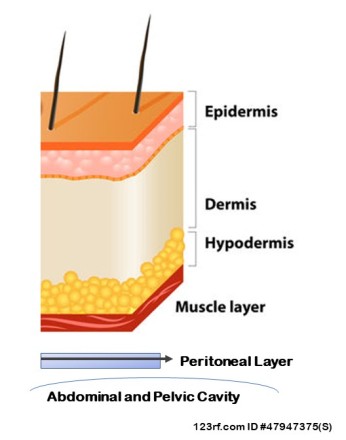

Anatomy:

The skin is the largest organ of the body. It’s comprised of many layers. Each tissue is composed of different types and combinations of cells. These layers include:

Epidermis: contains pores for sweat glands and hairs, sensory nerves to detect temperature, pressure and pain.

Dermis: contains sweat glands, and bundles of hair roots with sebaceous glands, blood vessels with tiny muscles to control hair movement.

Hypodermis: contains blood vessels and fat. Insulation.

Specific to the abdomen, multiple layers of muscles and fascia are located between the skin and abdominal cavity. Between the innermost muscle layer and the abdominal cavity is the peritoneum.

History of Cutaneous Endometriosis:

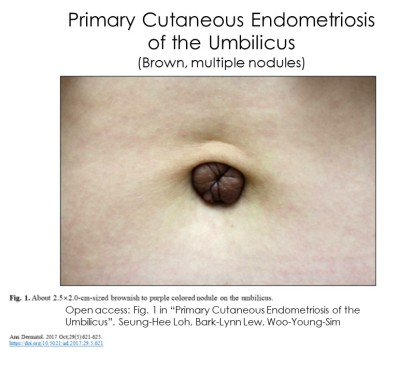

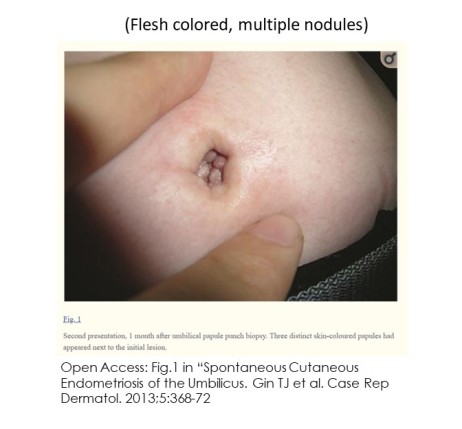

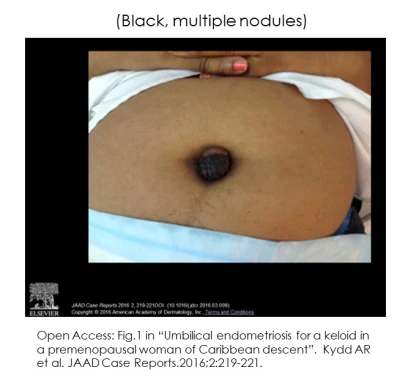

Daniel Schroen, MD is credited with the first description of Cutaneous Endometriosis (skin) in 1690 AD, Germany. (1) The first lesion localized to the Umbilicus (belly button) is was credited to the physician who first identified it in 1886. Lesions of the belly button are referred to as a ‘Villar’s Nodule’. (1,2,3)

Nearly all reported cases of skin endometriosis has involved the abdomen and groin, with exception to the female, and rare cis male, external genitalia. Over 100 case and small size studies have been published by 2009.(3)

No two lesions are the same. Lesions vary by depths of penetration, size, hormone receptivity and the tissue layers affected by the lesion (epidermis, dermis, subcutaneous fat, muscle, fascia).

Between the muscles and abdominal cavity lies the ‘peritoneum’. The peritoneum is a layer of fascia, lining the abdominal and pelvic cavities from respiratory diaphragm to pelvic floor.

Abdominal Wall – AWE (muscle) and female external genitalia are both Cutaneous Endometriosis . Many aspects of Cutaneous Endometriosis apply to to these lesions with exception to location and all tissues involved. In fact, researchers frequently interchange CE and AWE. Other researchers determine AWE as a lesion which remains in the sucutaneous tissue and muscle. The aspects unique to Abdominal Wall Endometriosis and External Female Genitalia are discussed below.

Cutaneous Endometriosis of the Abdomen:

Two categories of endometriosis are found in the abdominal skin:

- Primary (spontaneous)

- Secondary (iatrogenic-result of a medical procedure)

Primary (spontaneous) endometriosis

-is present in tissue and direct surrounding area without a history of prior surgical procedure and scar development.

Secondary (iatrogenic) endometriosis

-is found in or direct proximity to a scar. They occur most often in scars from prior surgical procedure of the uterus. Surgical procedures include:

- Laparoscopic-assisted Vaginal Hysterectomy

- Hysterectomy via laparotomy

- Ceasearean Section (Pfannenstiel Scar)

- Myomectomy through laparoscopy or laparotomy

Secondary endometriosis is theorized to begin from misplaced cells of the internal uterus (endometrial layer) transferred to the dermal layers of an incision during a surgical procedure. (1,4)

During the literature review to compose this page, two separate reports referenced that an endometriosis lesion in vicinity/on a scar can only be ‘secondary endometriosis’ if it appears within two years of the surgical procedure that created the scar. Unfortunately the citations given do not provide clarification of this time frame as a universally accepted time constraint. (5,6)

Locations:

Primary and Secondary Cutaneous Endometriosis are found in numerous areas of the abdomen. The Umbilicus is the most common location for Primary and Secondary. (2,3,5-14) Less frequent are: Laparotomy/C-Section Scars (15); Inguinal (16,17) and both Lower Abdominal Quadrants.(5) A single case of Primary Cutaneous Endometriosis of the Mons Pubis (18) and Pubic Tubercle (16) have been reported.

Prevalence:

Cutaneous Endometriosis is considered a rare form of disease. Current estimates range between .5-1% (umbilicus) (2,3,7,19), .4 – 4.0% (20), 5.5% (1,7) and .04 – 12% (21). It is suggested that higher prevalence is recorded in areas with greater awareness and more surgical procedures. (20) Numerous publications infer that only a small portion of persons with cutaneous endometriosis have concurrent pelvic disease compared with those with a solitary lesion of the skin. (4,13,16)

“Primary umbilicus endometriosis is initially very rare condition, but is now increasing in number”. (20) -Seung-Hee Loh et al. (2017)

Secondary lesions are far more common. An estimated 60-70% of all lesions are Iatrogenic (caused by medical examination or treatment). Only 30-40% of all Cutaneous Endometriosis is Primary (spontaneous). (7-12,16,20) Umbilicus lesions are documented long before laparoscopic procedures were invented. Today, the Umbilicus is often used as a portal (incision site) for minimally invasive surgery. With the Umbilicus the most common location for both Primary and Secondary lesions, there should be some hesitancy to conclude a lesion in/near an Umbilical scar is always iatrogenic (Secondary). The fact that the Umbilicus itself is a natural scar of the Umbilical Cord which separates shortly after birth. Based upon this:

“It is hypothesized that the umbilicus, even in the absence of iatrogenic manipulation, represents a physiological scar that may support the development of ectopic endometrial tissue. Alternatively, metaplasia of local tissue or activation and differentiation of precursor cells may explain the formation of endometrial tissue. It remains to be elucidated if additional factors in the local tissue environment participate in the development and propagation of endometriosis, either by facilitating transport, encouraging local metaplasia, or driving differentiation in the absence of the postoperative healing process.” (11) – Kydd AR et al (2016)

What causes cutaneous (skin) endometriosis?

Multiple theories about Primary (spontaneous) Cutaneous Endometriosis exist. One theory considers structural differences in the abdominal wall at the umbilicus (belly button). The area underlying the Umbilicus is significantly thinner than any other area of the abdomen. This may allow endometrial cells travelling through the abdominal cavity to become lodged.(1) Other theories suggest endometrial cells arrive to the skin through the vascular and lymphatic systems (1,3,19) or local transformation of residual cells located within the physiological scar created at separation of the umbilical cord (urachus) undergoe metaplasia (change from one type of cell to another). (1-3,19)

“The main etiology of endometriosis is not clear, but many studies suggest the hematogenous or lymphatic spread of stem cells from bone marrow or coelomic metaplasia” (15) – Alnafisah F et al. (2018)

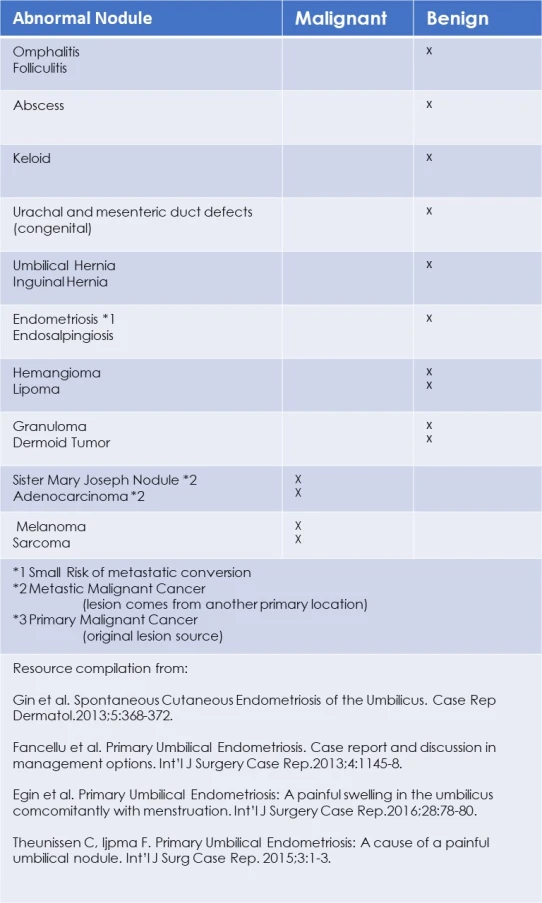

Differential Diagnosis:

A variety of benign and malignant cysts, tumors and defects grow on the abdomen and Umbilicus. The chart below lists lesions, conditions and cancerous status. (4,7,10,12)

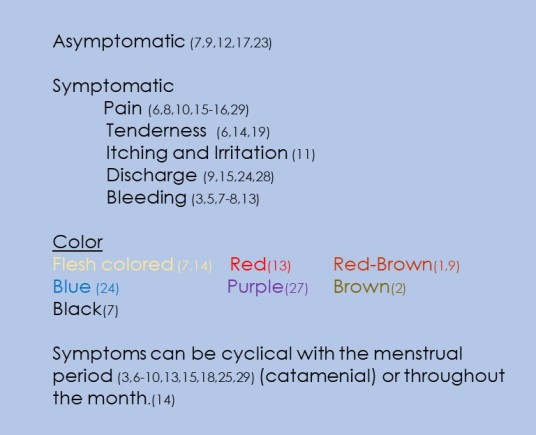

Clinical Presentations:

Skin endometriosis occurs in persons with (5,16,17) and without pelvic endometriosis (9-13,16). Lesions can be a single (3,7,10,12,23) or multiple nodules (7-8.11,20,23-26). Diameters range between a few millimeters to many centimeters (ie 6-7cm). (5) Other characteristics include:

“It is essential to point out that cyclicity is not always demonstrable and is not essential for diagnosis.” (16) – Agarwal A. (2008)

Persons with skin lesions occur across a range of age, history of pregnancy and diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis:

- Age range (23 (2) to 55 (27))

- History of pregnancy: None (nulliparous) (6,10-11,21,27-29) to multiparous (3,19,28)

- Previous diagnosis of pelvic disease or symptoms that suggest disease. Primary (2-4,6,10,13-14,20-21,25) and Secondary (2,21)

- Isolated abdominal endometriosis (3,9-10,12,13).

Need for Imaging:

“Management plans are not usually altered by imaging results, and a physical exam appears equivalent to imaging for a diagnosis of abdominal wall masses”

“With regards to recommendations for preoperative imaging, we believe that AWE is largely a clinical diagnosis. However, imaging studies may be necessary in cases in whom a hernia is strongly suspected or if concerns for extensive disease involving the fascia may require mesh reconstruction. Additionally, in clinical cases with an obvious mass but pain at the source of a prior incision it is reasonable to perform imaging to rule out subfascial AWE” (21) – Ecker A et al (2014)

According to the literature, imaging is adjunctive, but not essential tool for the diagnosis of cutaneous endometriosis. However, imaging can be advantageous for preoperative planning to determine the depth of lesion for reconstructive purposes, and most important, differentiate in lesions suspicious for malignancy. Despite the very minute probability an endometriosis lesions will become malignant, in these cases, extensive additional imaging is appropriate. (Further details at Link below: Endometriosis, Risk for Cancer and Malignant Conversion).

Does Cutaneous Endometriosis suggest presence and/or severity of pelvic endometriosis?

For ethical reasons, persons who don’t present with symptoms of pelvic endometriosis do not undergo unnecessary surgery to determine if asymptomatic disease is present. This creates a dilemma for accurate prevalence of those with isolated cutaneous lesions, those with concurrent pelvic disease and any correlations with disease severity. For most studies, persons who deny presence or history suggestive for pelvic endometriosis, based upon questionnaires, are presumed to have isolated endometriosis of the skin. Literature review in preparation of this page found very few studies performed laparoscopy to confirm presence of pelvic endometriosis. Further, laparoscopy was limited to those who reported symptoms. A single study of 10 cases reported their findings. All 10 subjects had undergone laparoscopy.

A study of 10 cases of cutaneous endometriosis, 4 primary and 6 secondary reported all patients (4/4) with primary (spontaneous) endometriosis had moderate to severe pelvic endometriosis. compared to only 2/6 persons with secondary (scar) endometriosis had concurrent mild to moderate pelvic endometriosis.” (16)

Does long term OCP promote CE among some persons?

It is worth further investigation for any association or correlation between long term oral contraceptive pill (OCP) use and primary cutaneous endometriosis.

Case 1:

A 30 yr old female reported continuous use of OCP’s for 7 yrs. A year after she discontinued using OCP, she developed a progressive ache and tenderness in the umbilicus. She identified a single nodule. She had no history of surgery, denied family history of gynecological disease and symptoms of pelvic endometriosis with exception to oligomenorrhea (for which she was receiving OCP for). (14) –Elm K. et al (2007)

Case 2:

A 27 year old female with early-onset menses (age 11 yrs), began using OCP at age 16 yrs (30 ug ethinylestradiol (30EE) + 2mg dienogest (DNG)). After 10 yrs continued use at this dose, she changed to a formulary (50 ug ethinlyestradiol (50EE) + 1mg chlormadinone acetate ) in traditional application of 3 wks on and 1 wk. off for menses. A year before she changed OCP’s , she reported progressive cyclical pain and ‘red, pus-like’ discharge from a single nodule. This continued a second year in addition to the onset of migraine headaches during the ‘off-week’ with the new OCP. Her medical provider recommended discontinue the current, higher dose OCP with interval breaks and restart the original lower dose OCP without interval breaks. The patient chose to continue at higher dose OCP with interval break instead, for another 5 months then completely discontinued all OCP use. The patient became pregnant immediately following discontinuation of the OCP. However, at 8 wks. gestation, she was reassessed. The umbilicus lesions had increased in pain, size (expanding to 3 nodules .5, 1.0 and 1.5cm), and reddish-purple that continued to bleed. Spinal anaesthesia was used to remove the lesion. Shortly after the procedure, the fetus died in-utero. As she continued to deny symptoms of pelvic endometriosis no laparoscopy was performed. (25) -Wiegratz I et al (2008)

Primary Cutaneous Endometriosis during Pregnancy

Two cases of Primary umbilical endometriosis during gestation have been reported (30).

Case #1:

An umbilical lesion developed during the 16th week gestation. A biopsy confirmed endometriosis. The lesion was monitored throughout gestation with spontaneous resolution two months after biopsy. No recurrence was observed through the late post-partum period.(30) – Razzi S. et al. (2004)

Case #2:

The woman’s first gravida. The rapid growth of the lesion, required surgical excision with an spinal anesthesia while the woman was still pregnant. In this case, the fetus died shortly after the procedure with gestation abruptly terminated. (25) – Wiegratz I et al. (2008)

Medical Management prior to excision of Cutaneous Endometriosis:

To date there is mixed findings in regards to whether short-term use of GnRH’s preoperative are beneficial. Some report their use prior to surgery is effective for pain (3,9,11) and size reduction. (3,9) These authors support the theory that preoperative use reduces risk of residual disease and regrowth after excision. In contrast, others oppose their preoperative use and reported increased residual disease and regrowth following use of GnRHa. (16) It’s important to note this study did not analyze lesion size as variable for recurrence following excision.

“In general, medical treatment using progesterone, danazol, norethisterone and GnRH analogs has not shown reliable results although some authors have reported some success in relieving symptoms and reducing the size of the endoimetriosis nodule”(4) – Fancellu A. et al (2013)

In other studies, the relationship between lesion size and recurrence were measured (but not any relationship to preoperative hormone use) among those with Secondary lesions. Those with lesions ❤ cm diameter had increased risk 7.8% of recurrence (31). Most interestingly, recurrence was higher among smaller lesions. (31)

“The treatment choice is wide excision such as abdominal wall musculature involvement necessitating enbloc resection of myofascial elements. Oral contraceptives, progestins, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRHa) all have been tried with minimal success as medical management.” (22)

Limited effectiveness of hormone manipulation to fully resolve endometriosis lesions may be due to its cellular composition. (11)

“Studies comparing the concentration of hormone receptors in ectopic and intrauterine endometrium note a lower concentration of these receptors in ectopic endometriosis, which may partially explain the poor response rates to medical therapy.” (16) – Attia L et al. (2010)

Surgical Management of Cutaneous Endometriosis:

Umbilicus Endometriosis:

“Treatment options are either local excision of the lesion or removal of the whole umbilicus (omphaloectomy) with or without laparoscopic exploration of the peritoneal cavity. The decision should be tailored for the individual patient. Taking into consideration the size of the lesion, the duration of the symptoms and the presence of possible pelvic endometriosis.” (4) – Fancellu A. et al (2013)

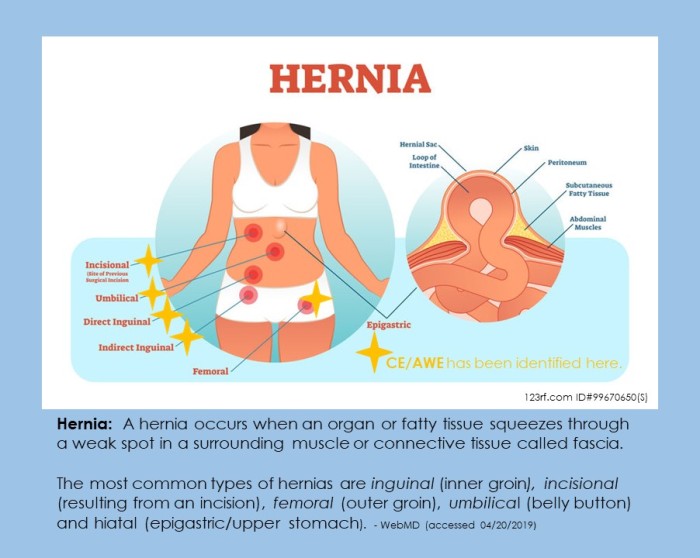

Some presentations may require multiple forms of imaging to rule out malignancies; concurrent hernia or elevated risk of formation after surgical excision; and measurement of lesion depth of penetration through the abdominal wall tissue layers. Circumstances occur in which surgical reconstruction is necessary following the excision of endometriosis nodule(s). In addition to the Pfannenstiel Scar (Caesarean section) and laparoscopic incision scars, endometriosis can occur concurrent with various types of hernias. (17)

“laparoscopic exploration has been advocated in order to exclude possible further foci of intraabdominal endometriosis, since pelvic endometriosis cannot be definitively excluded on transvaginal ultrasound or clinical examination. However, laparoscopic exploration remains debatable in asymptomatic patients”(4) – Fancellu A. et al. (2013)

Endometriosis, Risk of Skin Cancer and Malignant Conversion of CE.

A very small risk for malignant conversion of Cutaneous Endometriosis lesions exists. In addition, it is reported that those with any diagnosis of endometriosis has an elevated risk of developing malignant skin lesion(s). To learn more, please select here: Endometriosis and Skin Cancer

Abdominal Wall (Muscular) Endometriosis (AWE):

Abdominal Wall Endometriosis is a type of Cutaneous Endometriosis. Cutaneous Endometriosis involves the outer layers of the skin (epidermis, dermis and often the subcutaneous fat layer. Although not all studies distinctly separate AWE based upon tissue layers involved, most often:

“Abdominal Wall Endometriosis (AWE) is used to indicate the presence of ectopic endometrium located far from the perineum, embedded in the subcutaneous fatty tissue and the abdominal wall muscle layer” (23) – Savelli L. et al (2012)

AWE is similarly reported among those with (32-34) and without (35-36) a surgical history. The authors of one case declare that the lesion under investigation should be considered spontaneous (primary) despite a history of caesarean section. Their arguments is not in regards to a time factor greater than 2 years, but due to the lesion’s remoteness from surgical scar. (33) Literature review has revealed a sense of casual classifications of Primary and Secondary lesions. Time duration since formation of surgical scar and remoteness of a lesion from a surgical scar are two examples of authors identifying their case reports as Primary despite a remote history of surgical scar formation that other authors would report as Secondary lesions. On a large scale, the lack of formal criteria for Primary vs Secondary lesions impacts the value of collected data.

Endometriosis lesions up to 7 cm diameter were reported during our search of databases. (36)

Differential diagnosis of abdominal wall masses include:

- Abscess

- Lipoma

- Hernia

- Abdominal Wall Endometriosis (AWE) (32)

Sclerotherapy:

Cutaneous lesions are routinely excised to relieve symptoms. A single case of sclerotherapy is reported which successfully treated symptoms associated with a secondary cutaneous endometriosis lesion. Following biopsy to confirm the 3cm x 1.5cm growth within a 7 yr old ceasarean scar, the lesion was injected with Ethanol. (34) The authors contribute the small size and location of lesion contained completely within the muscle reduced risks and good outcomes. They also clarified sclerotherapy should be reserved for cases which are high surgical risk, during pregnancy or the patient refuses surgical excision. Sclerotherapy comes with significant risks to include the risk of abdominal wall necrosis (death) if treatment of larger lesions and risk of chemical peritonitis if entry into the abdominal cavity.

Patient Perspective:

My Rectus Abdominus (muscle) endometriosis was found by ultrasound. Although it was a small mass, the pain was much greater than my endo pain elsewhere. I’m not sure if this is because of the cutaneous nerve interaction or because I also had an inguinal hernia in this area. The surgeon felt this lesion followed a surgical track. The pain was searing and occurred when I engaged the surrounding muscles. Turning in bed, getting up from lying down and sneezing were very painful.

I have a large dog that needs a good walk. Several times I slipped on icy sidewalks. Just a little slip made my abdominal muscles contract, stopping me in my tracks. It felt like a hot knife slicing through my muscle. I would stop and breathe through the pain before continuing. The burning sensation would linger and my abdomen would swell. It would remain swollen for at least a day. ” – Bonnie A. (2019)

The same theories of origin apply to AWE which were mentioned above. Reference was made to prior case of male with cutaneous endometriosis in which it was hypothesized that the:

“Abdominal Wall Endometriosis can arise in a male from the prostatic utricle, which is a remnant of the uterus from the time when the male and female urogenital systems in the embryo are separated between the 8th week and 4th month” (AWEC) – Kocakusak A et al (2005)

Abdominal Wall Endometriosis in a Human Male:

About 20 cases of endometriosis among males has been reported since 1971. A single case of abdominal wall endometriosis was excised from an 83 yr old man with a history of prostate cancer. (37) Over a 10 year post-operative period he had received oral estrogen based medication. Unlike most cases of endometriosis among males, this person did not present with dormant cells from development while still in the womb. These dormant cells (embryonic rests and Mullerian Ducts) are involved in most male cases.

To learn more about Endometriosis in Males: Endometriosis in Males

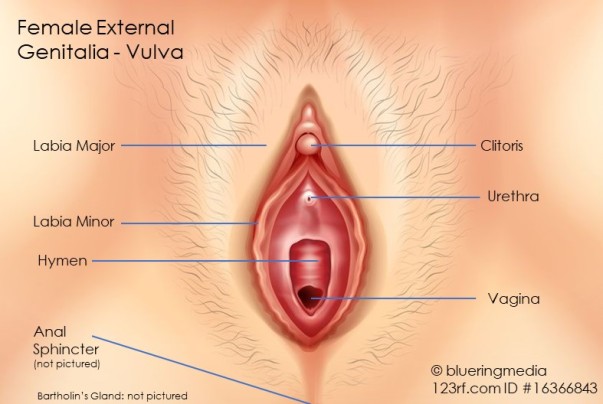

Endometriosis of the External Genitalia in Females:

Despite nearly 100 years after the first case of endometriosis in the perineal area was reported back in 1923 by Scheckele, like endometriosis, the exact origins of what and how the external genitalia among all mammals, regardless of gender, is still unknown. Only recently it is comfirmed that cells the external genitalia develop from ALL THREE primitive germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm), created in the early weeks following fertilization, are involved in formation of the external genitals. (38,39) Why is this significant?

One of the theoretical attempts to explain development of endometriosis centers around metaplasia. Metaplasia is the transformation of one type of cell, or intended destination cell, into another. Cells involved in this process originate from the same type of stem cells. In consideration of endometriosis, the cells involved in this process originate from the mesoderm. To date, the structures of the vulva are not fully clarified in regards to which specific structures and the proportions which arise from the mesoderm.

Like cutaneous endometriosis of the abdominal area, both spontaneous (40-44) and iatrogenic forms (45-49) (result from medical intervention – ie surgery), of endometriosis at the external genitalia area of females have been reported.

Cutaneous Endometriosis comprises a very small percentage of endometriosis (abt. 1%) among all disease areas. A similar proportion of Perineum/Vulva Endometriosis among all Cutaneous Endometriosis occurs. The incidence of comorbid pelvic endometriosis among those with cutaneous endo, regardless of body region involved tends to be very low. Rates similar to that reported by Wang Hanbi et al of 16.7% in a sample of 30 subjects is common. (50)

Iatrogenic lesions (secondary) are significantly more common (ie. episiotomy scars) followed by trauma (open wounds/sores) and last, spontaneous (primary) lesions. The majority of lesions on episiotomy scars develop many years following the procedure. (47)

Endometriosis lesions, regardless of origin, have been identified in numerous structures within the vulva.

Structures identified have included:

Vulva includes: Labia Majora and Minora (40,41,44), Vagina (46), Hymen (42), Bartholin’s Glands (46). Lesions found at the episiotomy scars have varied in depth of penetration from subcutaneous (47,48,49) to invasion of the pelvic floor musculature (45)

Lesions can also involve the anal sphincter. (50-54)

If the anal sphincter is involved, there is a risk of both incomplete lesion removal and fecal incontinence with surgical intervention. (53) Wide Excision reduces the risk of disease recurrence but increases risk of fecal incontinence. (51,52,54) Narrow excision reduces risk of fecal incontinence but increases risk of disease recurrence. (51) In these cases, surgical reconstruction (sphincteroplasty) may be necessary to reduce the probability of fecal incontinence following excision. (52) Wide excision involves removal of a zone of normal tissue around the lesion to ensure no residual lesion cells are left behind.

As with endometriosis of the abdominal area, lesions which develop on/direct vicinity to surgical scars or areas of prior open wounds (ie. ulcers) are theorized to occur from direct transplantation. (44-49)

The existence of primary case reports in persons without history of surgical trauma or open wounds maintains that direct transplantation cannot explain all presentations of disease. (40-42,44) Thus the probability endometriosis develops from multiple origins is highly likely.

The considerations for how endometriosis lesions form within gynecological procedure scars (ie. episiotomy, caesarean section and laparoscopy ports) is summarized as follows:

“The theory of direct implantation is widely accepted by many authors. Other theories argue that an endometriotic node in scars occur because of scar tissue metaplasia (primitive mesenchymal cells [from mesoderm cells] would differentiate to endometrial cells) and other hypothesis defends migration through lymphatic or vascular vessels to distant sites” (55) -Vellido-Cotelo R et al. (2015)

As declared previously, lesions which occur spontaneously, cannot form as a result of cells being transferred/transplanted from other reproductive tissues as a result of surgical procedure. Although our database search identified one case among an adolescent female who presented with history of prior abscesses at the vulva, (43) in which direct transplantation must be considered as possible origin, all other case reports occurred among women without surgical history or open wounds among the genital area.

“…perineal endometriosis without perineal trauma is believed to be associated with multiple factors, especially benign lymphatic metastasis. However, other factors, such as immunological, genetic and familial could be involved in the pathogenesis of this disease”. (40) -Hamdi A et al. (2015)

Other theories with some overlap of explanations include:

“Presence of endometriosis in the labia majora can be explained by the direct spread of endometriosis along the round ligaments. A solitary focus in the Bartholin’s Gland may theoretically be attributed to coelomic metaplasia or spread along lymphatic or vascular channels”. (46) – Singh P. (2017)

Treatment for Endometriosis of the External Genitalia

The same principles apply in use of hormone suppression. Hormone suppression may alleviate symptoms but will not resolve the lesions. (40,41)

Cutaneous Endometriosis Citations

Do you want to talk with others with the similar disease?

Extrapelvic Not Rare Endometriosis Education and DiscussionGroup

All Rights Reserved © 2019 Wendy Bingham, DPT Extrapelvic Not Rare